Months after this post, I am still banned from WebMD for my own good, but luckily for me, the New York Times prints plenty of fascinating medical information. This article was one example. The article talks about a variety of doctor behaviors that patients dislike, and the lack of feedback on these behaviors that doctors have traditionally gotten, as patients often just leave for a new doctor without giving a reason. In the article, some medical groups that have implemented patient surveys as a way to counter this problem share their experiences.

Dr. Howard Beckman, medical director of the Rochester Independent Practice Association, often talks to doctors who receive low scores in patient satisfaction – often, he says, on measures of how well patients thought they were listened to. He described his surefire method as “You use continuers. As you’re working with people, you say ‘uh huh’ three times.” And then he went on to describe doctors who tried this and discovered that they were able to get closer to the heart of the problem. One doctor talked with a patient who initially complained of chest pains. The doctor said “uh huh” the first time and found out that the patient also suffered from headaches. He said “uh huh” again, and the patient finally mentioned that the pains started when his brother died unexpectedly. The doctor was stunned that it worked – and while he might still order the same medical tests, he had a lot more context for what those results might mean than if he had immediately concluded that the man had a heart or head ailment.

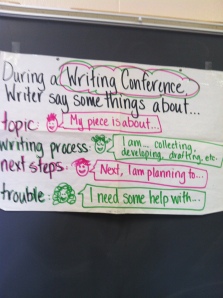

When I read this anecdote, I immediately thought about conferring. Specifically, research. How often, I wondered, had I bulldozed past a kid’s thinking by rushing the research? How often had I heard a likely teaching point emerge from a kid’s first remark and felt relieved (“Finally, a conference where I know what to say!”) and then cut the research short, maybe too short?

In one of those fortuitous “When you have a hammer every problem looks like a nail” moments, I then picked up a professional text (which I highly, HIGHLY recommend – imagine a professional book that you read on the train and can’t put down!), Reading Projects Reimagined by Dan Feigelson. On page 31 he said “Like Russian dolls, one inside the other, when a teacher continues to ask for elaboration in this way, by the third or fourth say more about that, the reader’s thinking is almost always deeper.”

So I started to try this out. I would say “uh huh” or “hmmm” or “Tell me more” three times, to see what would happen.

What didn’t happen was my secret fear — kids staring at me like I was out of my mind, or a little dumb. I worried that kids might think, “Why is she asking me to say more AGAIN?” but in fact, most of the kids I talked to seemed perfectly happy to go on and add more.

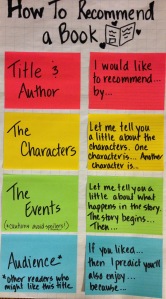

What did happen was that kids opened up more, and pushed themselves more. Instead of “Julian and Charlotte in Wonder are really different” and then a laundry list of reasons why, I started to hear “They both want attention.” Instead of “I could revise by changing my lead”, I got “Also, I could cut what doesn’t fit well, and I want to make it more exciting, and also I think this scene here could get better.” And instead of hearing the clock ticking toward desperately locating some kind of teaching point to use, I started to hear kids’ voices better.

It might seem that a simple prescription to say certain words in certain combinations couldn’t possibly be enough to make a meaningful change in my teaching practice. But the simplicity of the concept helped it to stick in my mind, and the response of kids when they were invited to talk more was worth the effort. Carl Anderson writes, “By truly listening to [our students] as we confer, we let them know that the work they’re doing as writers matters” (How’s It Going, page 23). The heart of conferring well is listening — so it’s worth doing whatever we can do to get kids to say more, and say more, and say more.